Regulars will be aware that I am presently working on an ambitious novel called Alpine Dawn. This book takes the reader back to the years immediately before the golden age of Alpine exploration--with my own unique fictional take on events, of course!

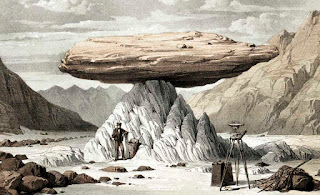

Here is the first draft of my "Prélude" for you to enjoy. Set in 1832, it depicts one of James Forbes' first expeditions to the Alps, in which he makes a discovery of tremendous importance that will shape events over the coming twenty years.

As always, this piece is very strictly "All Rights Reserved" and is unpublished and uncorrected draft material (very much subject to change and deletion!)

PRÉLUDE

1832

'I can see a body.'

'Do not be absurd, Monsieur. Nobody has passed this way for twenty years.'

'He is not lying in an artistic position, Couttet. Lower me some more.'

James Forbes gripped the rope with both hands. The fibres froze to his bare skin. After the heat of the glacier, up there in the open sun, it was a refreshing sensation. The guide, Couttet, lowered him in jerks and stops into the abyss. Slowly he sank into darkness.

Looking up, Forbes could see daylight still. The brilliant sky of an Alpine morning smiled down upon him, a spear of light thrown deep below the surface of the ice. As he descended, he passed from reality above into the dreamscape below: a glassy, cavernous wonderland of pearlescent blue and emerald green. Veins of trapped bubbles, frozen in whorls and spirals for vast spans of time, passed before his gaze. Meltwater streamed from the opening above and pattered on his cap before falling into the depths.

Crevasse. The word chilled and terrified him. The living did not venture into these places; they belonged to the dead, to demons and monsters.

Should I be doing this? It was not prudent, but the young Scotsman possessed insatiable curiosity and was determined in his quest for truth. Nobody knew why glaciers moved downhill, or even why they existed at all. Nobody had ever mapped one. Few learned men had ventured into the mountains since the war ended in 1815, and those who came here drew unscientific conclusions from their observations. Tourists clamoured to climb Mont Blanc but few looked at the glaciers with anything but facile awe.

There, he thought he saw it again! The impression of a man flickered before his eyes. A ghost, perhaps? He thought of the books he had read, chronicling the deeds of the old explorers: titans of the Enlightenment, champions of truth and science who had suffered for their cause. Could this be the shade of an old hero?

Gravel crunched under his boots as he reached solid ground. His eyes started to adjust to the subtle light beneath the surface, and he sensed a tunnel leading off to the left between mirrored walls. Droplets splashed in a pool:

plop plop, plopploplop, plop. He imagined such a sound continuing from the formation of the world until the present day, eternal and unchanging, and the thought thrilled him more than anything he had ever felt in his life. Although he aspired to be a man of science, he felt the more immediate presence of God in this underground cathedral.

Radiance surrounded and penetrated him, filling him with the most sublime awe and wonder at the glories of nature. Who could possibly have known that such beauty existed here, in the harshest and most ignored corner of Europe?

'I am untying from the rope,' he shouted. 'Wait for me, Couttet!'

Echoes vanished down the corridor. He followed them, seeking his ghost.

#

The rotting skeleton of a ladder blocked his path. Forbes stepped carefully towards it, wary of the slanting floor that dropped away into a dark fissure. The light grew fainter as the passage delved deeper. He raised his axe and smashed through the debris, slipping a sample of the wood into his pocket for later analysis.

Then he came face to face with his ghost.

A withered hand grew from the ice near Forbes' shoulder. It had caressed his coat before he realised it was there, and the gentle touch, like a whisper from another century, made him start. After crossing himself--the superstitions of the Alpine peasants had rubbed off after all--he took a moment to examine this grisly relic. An arm, all angular bones and leathery skin, reached from within the mass of the glacier. Beneath the surface, impressions of objects could be discerned, refracted and distorted in the packed ice. Was the body completely buried, Forbes wondered? If so, how had he been able to see it from the surface--?

He soon realised that the arm was entirely detached from the rest of the corpse, which stretched out at his feet, preserved more perfectly than he would have believed possible.

The man lay face down. He wore a tricorne hat and buckled shoes, studded with dozens of bright hobnails and fitted with six-pointed crampons for better grip. His coat was of poor quality and had been clumsily mended at the elbows and shoulders. A greasy ponytail poked out from under the hat. The left sleeve of his coat had been ripped off at the shoulder along with the arm, but of course there was no trace of blood. The long frost of this subterranean world had preserved him just as surely as an ice house. The skin of his cheek looked like a scrap of calf's leather, dry and long squeezed of any trace of life.

Forbes found himself transfixed to the spot, unable to move forward or back, compelled by some morbid power to look on the remains of his man who had died--how long ago? Forty years? Fifty? His clothing was not of this century.

Who was he? Few had ventured here since De Saussure had spent seventeen days on the ice in 1788. Forbes noticed an object to one side of the corpse that might be a knapsack. He stooped to open it, and items spilled out, releasing a cocktail of odours. Feeling with an outstreched hand, he sensed a woollen garment, a stone figurine (a saint, perhaps?) and a notebook...

By God, a notebook! He stood upright and opened it carefully. The pages were brittle with time, but he could see traces of handwriting. It was too dark to make out any words, so he fumbled in a pocket for his tin of friction lights. Sparks struck against the piece of sandpaper and soon a flame burst into life, driving back the natural radiance of the tunnel, replacing it with a chemical glow.

He turned to the last page of the book.

"Voyage sur la Mer de Gl. et le Col du Géant - 1788

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure et guides

Batons - 8

Haches - 2

Corde - 200 mètres

..."

It was an inventory for an expedition--the famous 1788 expedition! His hands shook. This was a momentous occasion. Had this poor man been one of De Saussure's guides? He scanned down the list of provisions until he came to a ruled line and a new title.

"VOYAGE SOUS LE GLACIER DE PÈGREMONT - 1789?

Batons - 12

Haches - 3

Corde - 500 mètres

Lanternes - 12

..."

Wait; journey

beneath a glacier? One lantern per climber? What was this--?

The match burned his fingers. He dropped it, and watched in horror as the flame engulfed the notebook, dry as dust after almost half a century. The burning pages fell from his hands and vanished into the dark.

Silence.

Forbes scrabbled at the grit and snow at his feet, desperate to recover something, anything, of that precious journal. His fingers came away smeared with soot; he found nothing but half a charred page, covered with meaningless numbers. The record of De Saussure's planned expedition--one that never took place--was lost forever.

Glacier de Pègremont.

The name haunted him. He knew the maps of the Alps, inaccurate as they were, by heart. There was and never had been any Glacier de Pègremont. Well, he had come down here seeking a ghost, but had not been prepared for this.

He looked at the poor guide whose name he still did not know. This brave man had died far from home in a barren and harsh place, induced here by the promise of gold from the wealthy Genevese scientist. Forbes liked to think some nobler sentiment stirred the heart of every mountain

voyageur. He shared a bond with this man. They had seen the same wondrous sights, smelled the same clean air, felt their hearts uplifted by the symphony of an Alpine dawn.

A sad end to a charmed life. All of a sudden he wanted to be out of this tomb, this frozen world of silence and the petrified dreams of the long dead.

'God be with you, brave fellow,' he whispered, and turned back towards the light.