In 1842, Professor James Forbes undertook an epic voyage throughout the Alps. In 2014, I replicated a 40 mile portion of that voyage: the segment between Aosta in Italy and Evolene in the Valais. In this blog post I'd like to tell you about my adventure and what I have learned about the dramatic changes to the ice world in the last 162 years.

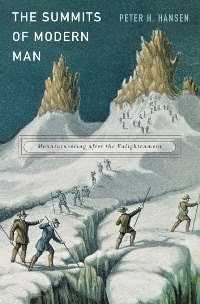

For those of you who might not be aware, Forbes is a main character in my

Alpine Dawn series (beginning with book 1,

The Atholl Expedition). In real life he was a prolific mountaineer, explorer, and geologist. In his many visits to the Alps he conducted pioneering work on the physics of glaciers and also helped to explore and map the higher regions of the Alps, particularly in the old territory of Savoy.

One reason I wanted to replicate this particular section of the journey was that it crosses the Col Collon, a high glacial pass between Italy and Switzerland. The section in Forbes' book regarding this pass is one of the most memorable; at the time of his crossing he believed he was the first explorer to navigate it, although evidence suggests it had been in frequent use by locals for hundreds of years.

Here's an overview map of my route.

Valpelline

My journey began on the 29th of June in the Italian city of Aosta. I hiked uphill for a few hours to reach the village of Valpelline, my first campsite and the true beginning of my journey. In 1842 Forbes found it to be a tiny settlement with no prospect of accommodation, but managed to secure a room in a friendly household. At that time travellers visited the area extremely rarely and Forbes commented that most of the settlements in the valley were badly afflicted by goitre and cretinism (common afflictions in the high Alps at that time).

The next morning I began the long walk to Prarayer. Most of the route is actually road walking these days but the scenery was so spectacular I hardly minded. The total ascent on my first full day was about 1,200m, and I passed through a number of small villages including Oyace (at a steepening in the valley) and Bionaz. The weather was sunny and very hot, the scenery rather more Italian than quintessentially Alpine.

|

| Typical Val Pelline terrain. The village centre frame is Oyace. |

At this point mountains of considerable height hugged the valley on both sides, but no glaciers were in evidence and little snow. Forests of larch and pine predominated, and the communities were generally agricultural and deeply traditional. In 1842 Italy as we know it today did not exist; this region belonged to the territory of Piedmont, part of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Bionaz

Forbes writes:

The village of Biona is the last of any size in the valley,— the last, I think, which has a church. We halted there, and made a hearty meal in the open air upon fresh eggs and good Aostan wine. The village of Biona is 5315 feet above the sea, by M. Studer's observation.

Bionaz remains a tiny hamlet clinging to the edge of a precipice, and indeed it hardly seems to have changed in the last 162 years. It had a peculiarity in the 19th century: virtually all of the male inhabitants were also named "Biona," and that was the name of the guide Forbes engaged there to take them over the Col Collon into Switzerland. They nicknamed him l'habit rouge due to his habit of wearing scarlet clothes at all times, which was apparently a common trait in the Pays d'Aoste at that time.

|

| Bionaz |

Prarayer

About an hour after Bionaz I reached the reservoir of the Lac des Places de Moulin, the waters of which are held back by an enormous dam. For the first time I gained a view of some of the 4000m mountains, notably Dent d'Herens, which rose as the highest point of a jagged chain above a glacier.

Forbes and his companions stayed at the "Chalets of Prarayon," today a hut known as the

Rifugio Prarayer. However, since the formation of the reservoir has obliterated the old road, necessitating a path slightly higher up the hill, I selected a campsite at a flat alp above a larch wood. It had excellent views of the nearby mountains and was a peaceful place to stop for the night.

|

| Camp one. Quite a view! |

|

| Alpenglow on the Dent d'Herens and satellite peaks |

The Comba d'Oren

My third day was rather short as I wanted to spend as much time as possible exploring the Comba d'Oren. This is a deep valley leading from Italy to the Col Collon and the border of Switzerland. In 1842 it was reported to be substantially occupied by a glacier:

It was an hour's walk to the commencement of the glacier, which fills the top of the valley, and which descends directly from the great chain. Having gained an eminence on the south-east side of the valley which commanded the glacier, I saw that the ascent of it must be in some places very steep, though, I should think, not wholly impracticable.

And:

We there find a deep gorge, completely glacier-bound at its upper end...

It's also interesting to note that, although the Comba d' Oren is only a few hours' walk from Valpelline and a day's ride from the city of Aosta (in 19th century terms), the region was almost completely unknown to explorers:

All our maps were here at fault ... no kind of resemblance to the outlines even of the great chain, and the passage must have been put down at random.

|

| The Comba d'Oren |

Today the Glacier d'Oren, which Forbes and his companions followed to the Col Collon, is dead. Only semi-permanent snow patches remain, and the other two glaciers in the valley have dramatically retreated. I think it very probable that in 1842 there was only one much greater glacier here.

In 2014 the ascent to the Col Collon travels over a variety of scree slopes and small snow fields. It's astonishing to think that in a mere 162 years what was once a large glacier has completely disappeared.

|

| The dead Glacier d'Oren. You can see the stubs of the Glaciers d'Oren Sud (left) and Nord (right) in the background. |

A night on the glacier

I reached the Col Collon (3069m) early in the afternoon and made my camp. The snow was fairly soft so I took my time digging out and consolidating a tent platform. This was actually my first experience of camping on snow with a tent!

|

| Camp Two, beneath the desolate cliffs of La Vierge. |

It was a wild location. L'Eveque (3716m) towers above, spitting rocks down its central colour every now and again. The Cairngorm-like expanse of Mont Brule (3578m) looked a bit more friendly, and my original plan was to get up before dawn the next morning and make an attempt on that mountain.

|

| Mont Brule |

However, the weather soon took a bad turn, and by late afternoon I was starting to wonder if camping on the col had been a wise idea after all.

|

| Bad weather coming in from Italy |

I made the decision to stay the night. The only reasonable alternative would have been to descend towards Arolla, but with an entire glacier to traverse I didn't fancy my chances of finding a better campsite before dark.

A spooky descent of the Haut Glacier d'Arolla

When I woke at 3am, I looked out of the tent and saw that the clag had come in fast, so I went straight back to sleep, not waking again until 7. However, between 3 and 7 quite a lot of snow fell (about 6 inches altogether) and when I awoke the second time my tent was almost buried in it. Visibility had reduced to about twenty feet.

|

| After digging the tent out |

Alone on a glacier at over 3000m and in dreadful conditions, I knew I had to get out of there pretty quickly! I struck camp in ten minutes flat and began the descent to the Haut Glacier d'Arolla in poor visibility. The fresh snow also made the going treacherous, balling up under my feet, but crampons were necessary due to the patches of bare ice on the slope.

|

| A rare view through a break in the cloud |

Fortunately, the Haut Glacier d'Arolla is an easy glacier, relatively flat for the most part and with no real crevasses to worry about. The navigation was no more challenging than a day out in the Cairngorms, and once I focused on my situation and started using the map and compass, the descent proved to be straightforward.

|

| The upper basin |

In 1842, Forbes and his companions found the corpses of no less than three people on or near the Col Collon, attesting to its popularity at the time amongst traders and (often) smugglers. The sight of the second skeleton particularly affected the guide Biona, who refused to return that way home by himself after that leg of the voyage:

The effect upon us all was electric ; and had not the sun shone forth in its full glory, and the very wilderness of eternal snow seemed gladdened under the serenity of such a summer's day as is rare at these heights, we should certainly have felt a deeper thrill, arising from the sense of personal danger. As it was, when we had recovered our first surprise ... we turned and surveyed, with a stronger sense of sublimity than before, the desolation by which we were surrounded, and became still more sensible of our isolation from human dwellings, human help, and human sympathy, — our loneliness with nature, and as it were, the more immediate presence of God. Our guide and attendants felt it as deeply as we. At such moments all refinements of sentiment are forgotten, religion or superstition may tinge the reflections of one or another, but, at the bottom, all think and feel alike. We are men, and we stand in the chamber of death.

Philosophising aside, the thing that truly struck me was the contemporary description of the Arolla glacier:

The glacier on which we now were stood is the Glacier of Arolla, that which occupies the head of the western branch of the Valleé d'Erin. It is very long ... The lower extremity is very clean, little fissured, and has from below a most commanding appearance, with the majestic summit of Mont Collon towering up behind.

Nowadays the "Glacier of Arolla" is no longer one single stream, but broken into two: "Haut" and "Bas," both of which are rather small by the standards of Alpine glaciers. I calculate that the snout of the upper mass is at least

two miles further uphill compared to its location 162 years ago, and moreover, the level of the ice has dropped significantly, leaving vast fields of scree and waste. This illustration from 1842 demonstrates what I mean very well, I think.

|

The Arolla glacier in 1842. Note the enormous convex snout,

evidence of a glacier until recently in advance; although Forbes noted

that it had already retreated from its recent maximum. |

|

| From a similar viewpoint today. The Haut Glacier d'Arolla has retreated completely out of view. |

It really is astounding to see direct evidence of glacial retreat on such a scale. The same story is being played out all over the Alps, and it just goes to show what a completely different world it was for the early Alpine explorers. They climbed in a time when the ice was much more extensive than it was today ... and yet even by the 1840s the glaciers were in retreat. The damage was being done two centuries ago.

|

| The ruins of the Bas Glacier d'Arolla |

Evolene

I reached Arolla fairly early in the afternoon so decided to keep walking. The weather remained misty and rather cold, and I followed the old road through the forest to Les Hauderes, and finally to Evolene, the ancient capital of Val d'Herens.

I first visited Evolene in 2010. It's something of a place of pilgrimage for me. In 1899, Owen Glynne Jones (the main character of my novel

The Only Genuine Jones) stayed at Evolene for an Alpine climbing holiday. He and three of his guides perished on the Dent Blanche during an attempt on the Ferpecle Arete. It was one of the worst climbing accidents of the 1890s and his remains were interred in the cemetery in Evolene, but certain relics, including his hat and ice axe, eventually found their way to the Alpine museum in Zermatt, where they can be viewed today.

Forbes, Studer and co also stayed at Evolene during their voyage. They found it to be an unwelcoming place:

We knew too well what accommodation might be expected even in the capital of a remote Valaisan valley to anticipate any luxuries at Evolena. Indeed, M. Studer had already been there the previous year, and having lodged with the Curé, forewarned me that our accommodation would not be splendid. The Curé, a timid worldly man, gave us no comfort, and exercised no hospitality, evidently regarding our visit as an intrusion.

They eventually managed to haggle a single bed, for which the travellers were obliged to draw lots; Forbes won, and poor Studer wouldn't admit where he had been forced to spend the night (probably in a hay barn). He was so traumatised by the experience that he cut his trip short and refused to accompany Forbes any further!

Fortunately my welcome in Evolene was somewhat warmer and I pitched my tent in exactly the same spot I found in 2010, at the campsite in the village. I spent a rest day wandering around the town and making notes — it hasn't changed much since the 19th century, after all — and reflecting on how lucky I had been to repeat this small fragment of Forbes' epic journey, to witness for myself how things had changed in the last 162 years, and enjoy three days of beautiful mountain scenery in the Alps.

Altogether, the route I took was about 40 miles. Strong walkers could easily do it in two days, particularly by taking the bus or driving to Valpelline itself instead of starting from Aosta on foot.

In a future blog post I will write up a trip report of the mountain I climbed from Evolene: Sasseneire, 3254.